How to Write a Technical Resume Without Making Up Metrics

Learn how to showcase technical achievements on your resume using context and clarity instead of invented metrics. Real impact beats fake percentages.

Most resume advice is built around one idea. Use the XYZ resume formula. What you did. How you did it. What changed because of it.

It’s great advice, and when it works, it works fast. It forces clarity. It cuts the fluff. It turns vague claims into outcomes a hiring manager can understand in ten seconds.

Here’s what nobody talks about. Most technical work doesn’t produce clean metrics. You fix a memory leak that was crashing the app twice a week. You refactor a module that three other developers were afraid to touch. You debug a race condition that only happened under specific load conditions. None of that has a percentage attached to it, but all of it matters.

The panic sets in when you read resume advice that screams “quantify everything” without explaining what to do when you can’t. So people start inventing numbers. They guess. They round up generously. They attribute improvements to their work that may have come from ten other factors.

That approach backfires. Experienced hiring managers can spot inflated metrics from across the room. What actually works is learning to communicate technical value without relying on numbers you don’t have.

You don’t need to pretend that every bug fix increased revenue by five percent. You don’t need to manufacture KPIs for work that was never designed to produce them. What you need is a way to describe what you actually did, why it was hard, and what became possible because you did it.

Let me share how to frame technical achievements in context and complexity. How to show real impact without artificial numbers. How to write a resume that gets you interviews by being clear and honest about the value you bring, even when that value doesn’t fit neatly into a percentage.

Why Most Technical Work Resists Clean Metrics

Software development is not a factory line where you can count widgets per hour. It’s a discipline built on problem solving in complex, interdependent systems where cause and effect are rarely linear.

When you fix a critical bug, you don’t always know how much money it saved. When you improve code quality, the benefit might not show up for months. When you architect a solution that prevents future problems, there’s no spreadsheet that tracks disasters that didn’t happen.

Product managers and data analysts have metrics baked into their roles. Revenue, conversion rates, user growth. These are direct outcomes tied to clear objectives. But if you’re a backend engineer maintaining infrastructure, your wins look different. Uptime. Stability. Faster deploys. Reduced manual intervention. These matter enormously, but they don’t always translate into percentages that sound impressive on paper.

"A strong resume doesn't need big numbers. It needs clarity that helps the recruiter understand what you actually contributed."

The nature of technical work makes measurement complicated. You might spend three days tracking down a bug that only affected two percent of users under very specific conditions. That small percentage doesn’t capture the severity. Maybe those users were enterprise customers. Maybe the bug was causing data corruption. Maybe it was blocking a major product launch. The number tells you nothing about the actual stakes.

Or consider refactoring. You spend two weeks cleaning up a mess in the authentication layer. The system works the same way it did before, at least from the user’s perspective. But now other developers can add features without breaking things. Now the test suite runs faster. Now onboarding new engineers takes less time because the code is actually readable. How do you quantify that? You can’t, at least not easily. But the work has real value.

Technical work often involves reducing risk, preventing failures, and creating conditions for other people to move faster. You catch a security vulnerability before it becomes an incident. You optimize a query before it starts timing out under production load. You document a system before the only person who understands it leaves the company. None of these have obvious metrics attached, but all of them prevent expensive problems.

The challenge is that hiring managers need to evaluate you somehow. They need to distinguish between someone who ships code and someone who solves hard problems. If you don’t give them a way to see that difference, they’ll default to surface level signals like years of experience or recognizable company names. That’s why learning to communicate technical value matters. Not so you can inflate your work, but so you can make the real value visible.

What Hiring Managers Actually Want to Know

Recruiters and technical hiring managers are not looking for your ability to generate impressive sounding statistics. They want to understand what you can do and whether you can solve the problems they’re facing.

When someone reads your resume, they’re asking silent questions. Can this person handle complexity? Do they understand the systems they work on? Can they diagnose problems that other people miss? Do they make things better or just maintain the status quo?

The answers to those questions come from context, not numbers. If you say “optimized database queries,” that’s vague and forgettable. If you say “rewrote slow reporting queries that were timing out during peak traffic, reducing page load failures and unblocking the customer support team,” that tells a story.

It shows you understood the problem, identified the root cause, and made a decision that had ripple effects beyond your immediate task.

Hiring managers are pattern matching. They’re looking for signals that you can think like an engineer, not just execute like one. When you describe fixing a bug, they want to know if you understand why it happened. When you mention building a feature, they want to see if you considered edge cases. When you talk about improving a system, they want evidence that you thought about maintainability and not just short term fixes.

This is why made up metrics backfire so badly. A hiring manager who sees “improved performance by 200%” without any explanation will wonder what you’re hiding. Did you improve performance from what baseline? Under what conditions? For which operations? If you can’t answer those questions, the metric becomes a red flag instead of a selling point.

"Your resume doesn’t need fake percentages. It needs clarity. Here’s what technical impact actually looks like when you can’t measure it in numbers."

What actually builds credibility is showing you can think clearly about technical problems. You don’t need to prove you’re brilliant. You need to prove you’re competent, thoughtful, and capable of working in messy real world conditions where the answer is not always obvious.

Good hiring managers know that not every problem has a number attached to it. They’ve worked in technical roles themselves. They understand that some of the most valuable work is invisible. Preventing outages. Reducing technical debt. Building tools that save everyone time. Making systems more understandable. These contributions are hard to measure but easy to recognize when someone describes them well.

The mistake people make is thinking hiring managers want to be impressed. They don’t. They want to be informed. They want to know what you’ve actually done so they can assess whether you’re a good fit for what they need. If you give them clear, honest, well written descriptions of your work, that’s far more useful than a resume full of percentages that might or might not mean anything.

How to Frame Technical Achievements Through Context and Complexity

Context is the bridge between what you did and why it mattered. Complexity shows the depth of the problem you solved. Together, they create a picture of your capabilities without requiring you to invent metrics.

Start with the situation. What was broken, slow, unreliable, or blocking progress? Then describe the challenge. Was it a poorly understood legacy system? A high stakes production issue? A problem that required cross team coordination? Finally, explain your contribution. What did you diagnose, build, fix, or improve?

If you debugged a race condition in a distributed system, that’s meaningful because race conditions are notoriously hard to reproduce and fix. If you refactored a critical module that everyone was afraid to touch, that shows you can navigate technical debt and reduce risk. If you built tooling that automated a manual process, you freed up time for your team to focus on higher value work.

The situation gives weight to your contribution. Fixing a bug in a low traffic feature is different from fixing a bug in the checkout flow. Optimizing a query that runs once a day is different from optimizing one that runs ten thousand times per hour. You don’t need to say the second scenario is more important. The context does that work for you.

Complexity signals expertise. When you mention specific technical challenges, you’re showing the hiring manager that you operate at a certain level. You don’t need to use jargon to sound smart. You need to describe the problem clearly enough that someone with technical knowledge can recognize it as difficult.

“Fixed database performance issues” tells me nothing about what you actually know. “Identified missing indexes on foreign key columns in high volume tables and added them during a maintenance window, reducing query times from several seconds to under 100ms” tells me you understand database fundamentals, you can diagnose performance problems, and you think about deployment risk.

The goal is not to make the work sound bigger than it was. The goal is to give the reader enough information to understand what you actually accomplished. A junior developer and a senior developer might both say they “fixed bugs.” The difference is that the senior developer explains which bugs, why they were hard, and what became possible once they were resolved.

You can also frame achievements through their scope or consequences. Did your work affect one feature or the entire application? Did it unblock one developer or an entire team? Did it solve an immediate problem or prevent future issues? These distinctions matter because they show how you think about impact beyond just completing tasks.

When you write your resume bullets, ask yourself if someone reading them could picture what you did. If the answer is no, add more context. If you’re worried about resume length, cut unnecessary words instead of cutting necessary details. “Collaborated with stakeholders to deliver solutions” can become “Worked with the support team to fix issues affecting enterprise customers.” Same length. Much clearer.

Real Results That Don’t Require Artificial Numbers

Impact is not always measurable, but it’s always describable. You can communicate the value of your work by focusing on outcomes that matter in technical environments, even when those outcomes don’t come with clean data points.

Think about what changed because of your work. Did you unblock another team? Reduce the frequency of production incidents? Improve deploy reliability? Make onboarding faster for new engineers? Reduce the time it took to diagnose issues in a specific part of the codebase?

These are real results. They’re the kinds of improvements that make teams more effective, systems more stable, and technical debt more manageable. But they don’t always map to revenue or user growth, and that’s fine. Not every role exists to move top line metrics.

If you improved code quality, you can talk about how that reduced the number of bugs introduced in later features. If you built internal tooling, you can describe what manual work it eliminated. If you mentored junior developers, you can explain how that improved team velocity or code review quality. All of these have value, and none of them require you to pull percentages out of thin air.

One way to think about technical impact is through what becomes possible afterward. Maybe you migrated a legacy service to a new framework, and now the team can add features without fighting with outdated dependencies. Maybe you standardized error handling across microservices, and now debugging production issues takes half the time it used to. Maybe you wrote documentation for a complex system, and now new hires can contribute to it within their first week instead of their first month.

Another form of impact is risk reduction. You caught a security flaw during code review before it reached production. You identified a scaling bottleneck before traffic grew enough to trigger it. You added monitoring to a critical service that previously failed silently. These contributions prevent bad outcomes, which is harder to quantify than creating good ones, but just as valuable.

"Most technical work doesn't produce clean metrics. Uptime, stability, reduced risk. These matter enormously, but they don't fit on a spreadsheet."

Sometimes the impact is about improving the developer experience. You set up automated tests that catch regressions before they reach staging. You created a script that automates a tedious deployment step everyone hated. You reorganized the codebase so related functionality lives together instead of scattered across dozens of files. These changes don’t show up in user facing metrics, but they make everyone’s job easier.

Stability and reliability are also real results. You reduced the number of times the on call engineer gets paged at night. You fixed flaky tests that were making the CI pipeline unreliable. You addressed memory leaks that were causing gradual performance degradation. These improvements might not have dramatic numbers attached, but they matter to anyone who has to maintain the system.

The key is being specific about what improved and why that matters. “Improved system reliability” is too vague. “Fixed intermittent connection failures in the payment processing service that were causing transaction timeouts” is specific. It tells the reader what was broken, where it was broken, and what the consequence was. That’s a complete picture of impact without needing to claim you increased revenue by some made up percentage.

What Clarity Looks Like in Practice

A strong resume does not rely on big numbers. It relies on precise language that helps the reader understand exactly what you did and why it mattered.

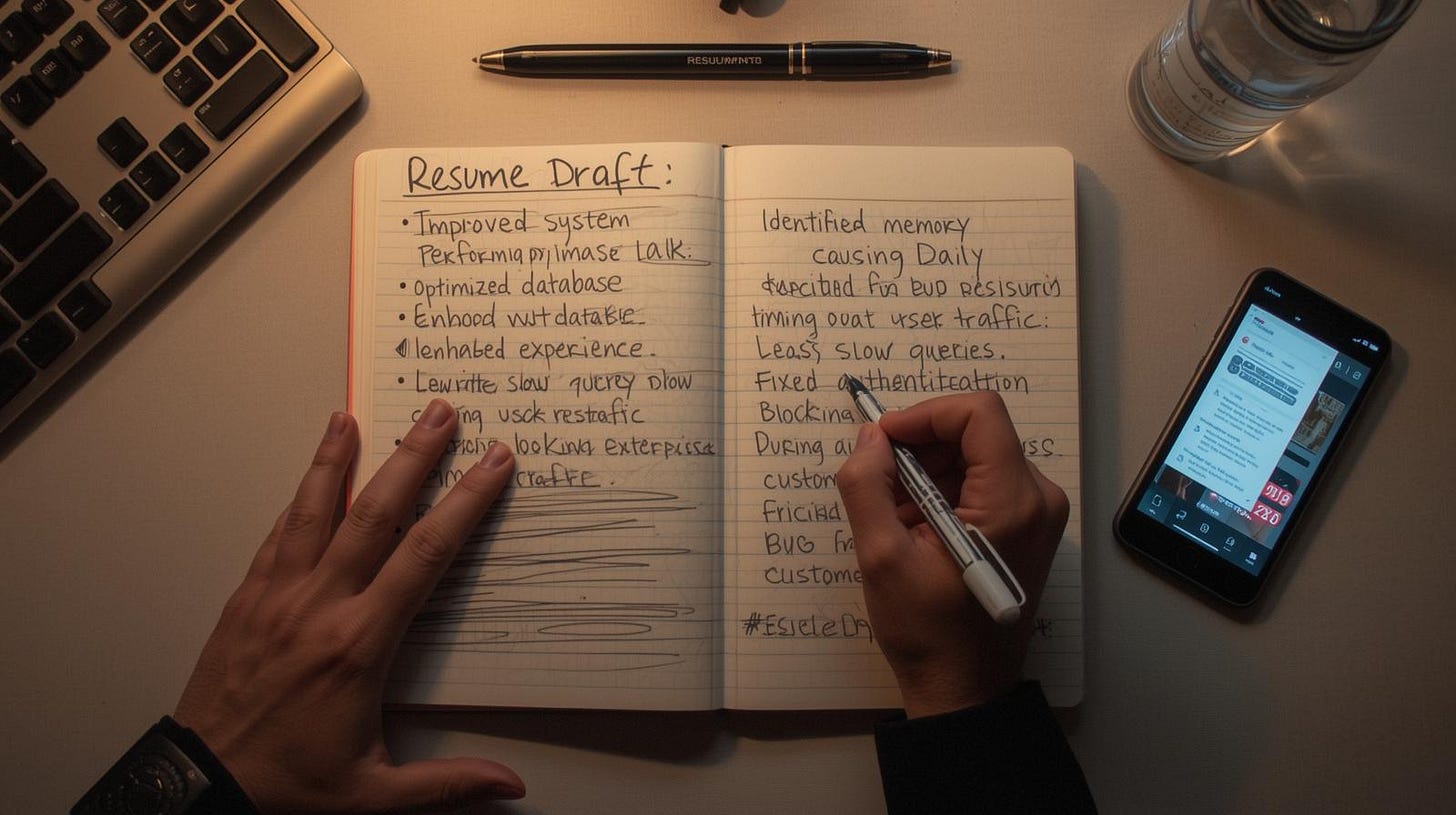

Compare these two bullet points. “Improved system performance.” versus “Identified and resolved a memory leak in the background job processor that was causing daily restarts and delaying customer notifications by up to two hours.”

The second one is not inflated. It’s specific. It tells you what the problem was, where it lived, and what the consequence was for users. It doesn’t claim the fix increased revenue or reduced costs by some percentage, because that’s not the point. The point is that the system stopped breaking, and that matters.

Or consider this. “Worked on API improvements.” versus “Redesigned the authentication flow for the public API to handle token expiration more gracefully, reducing support tickets related to failed integrations.”

Again, no invented metrics. Just a clear explanation of the problem, the solution, and the outcome. The reader can now picture what you did and why it was useful. That’s what clarity looks like.

Precision matters because vague language creates doubt. When you say you “contributed to” a project, the hiring manager wonders what you actually did. When you say you “helped improve” something, they don’t know if you led the effort or just watched. When you say you “worked with the team” on something, it’s not clear what your individual contribution was.

Clear writing removes that ambiguity. “Built the data export feature that allowed enterprise customers to download their usage history in CSV format” tells me exactly what you owned. “Debugged and fixed a threading issue in the image processing pipeline that was causing occasional crashes under high load” tells me what problem you solved and what skill you demonstrated.

“The goal is not to make the work sound bigger than it was. The goal is to give the reader enough information to understand what you actually accomplished.”

You can also be clear about scope. If you worked on one part of a larger project, say which part. If you collaborated with others, specify what you were responsible for. “Implemented the front end components for the new dashboard while the backend team built the API endpoints” is honest and clear. It shows you understand how your work fits into the bigger picture without claiming credit for things you didn’t do.

Hiring managers do not spend a lot of time scanning each resume. If they can’t quickly understand what you contributed, your experience gets lost in the noise. Clarity cuts through that. It shows respect for the reader’s time and confidence in your own work.

The best resume bullets answer three questions in one or two sentences. What was the problem or need? What did you do about it? What changed as a result? You don’t need to answer all three every time, but hitting at least two makes your contribution clear.

“Refactored the user authentication module to use a more secure token based approach” hits two. You describe what you did and hint at why it mattered. “Rewrote the search indexing process to run incrementally instead of rebuilding the entire index nightly, reducing server load and making new content searchable within minutes instead of hours” hits all three. Problem, solution, outcome.

This is not about writing longer bullets. It’s about writing tighter ones. Cut words that don’t add information. “Successfully implemented” is the same as “implemented.” “Effectively collaborated” is the same as “worked with.” “Utilized various technologies” tells me nothing. Every extra word that doesn’t clarify your contribution is a word that could have been used to explain what you actually did.

Clarity also means using concrete nouns and active verbs. “Made improvements to the codebase” is abstract. “Removed deprecated API calls and updated dependencies to current versions” is concrete. The second version tells me what “improvements” actually means in practice.

You Don’t Need to Invent Metrics to Stand Out

Strong resumes communicate value, not volume. The goal is not to have the most impressive sounding numbers. The goal is to make it easy for someone to see that you solve real problems and contribute in ways that matter.

If you have real metrics, use them. If you reduced deployment time from thirty minutes to five, say that. If you handled two hundred support escalations in a quarter, include it. But if you don’t have those numbers, don’t fabricate them. Instead, focus on the why and the how.

What systems did you work on? What risks did you reduce? What workflows did you improve? What problems did you solve that no one else wanted to touch? These questions lead to stronger, more honest bullet points than trying to attach percentages to work that doesn’t naturally produce them.

The best candidates are not the ones with the biggest numbers on their resumes. They’re the ones who can clearly explain what they’ve done and demonstrate that they understand the work at a deep level. When you interview, nobody is going to ask you to defend the percentage you claimed. They’re going to ask you to walk through your technical decisions, explain trade-offs you considered, and describe how you approached problems.

Your resume should set you up for that conversation. It should give the interviewer enough context to ask good questions about your work. If your bullets are vague or inflated, the interview becomes an exercise in damage control. If your bullets are clear and honest, the interview becomes a chance to go deeper into the interesting parts of what you’ve built.

Technical hiring is about finding people who can think, adapt, and contribute in complex environments. Your resume should reflect that. It should show that you understand the problems you’ve worked on, that you can communicate clearly about technical topics, and that you make things better wherever you go.

Think about the engineers you respect most. They’re probably not the ones who talk about their work in exaggerated terms. They’re the ones who can explain complicated things simply, who admit when something was harder than expected, who give credit to others when it’s due. That’s the tone you want on your resume. Confident but not boastful. Specific but not drowning in jargon. Honest about what you did and why it mattered.

“Strong resumes communicate value, not volume. The goal is not to have the most impressive sounding numbers.”

Standing out does not mean having the flashiest resume. It means having a resume that makes the hiring manager think “I want to talk to this person.” That happens when your experience is presented clearly, when your contributions are described in ways that demonstrate competence, and when your bullets show you think about more than just finishing tickets.

You stand out by being clear when others are vague. By being specific when others hide behind buzzwords. By being honest when others inflate. That combination is rare, and hiring managers notice it.

That’s what gets you interviews. Not the biggest numbers. Not the flashiest claims. Just honest, clear, well written descriptions of work that actually mattered. Work that solved real problems. Work that made systems better or teams more effective. Work that you can talk about with confidence because you actually did it and you understand why it was valuable.

If your resume reflects that, you don’t need fake metrics. You already have something better. You have clarity. And in a sea of inflated, generic, buzzword filled resumes, clarity is what makes you memorable.

How to Write a Technical Resume

Writing a resume without inflating metrics is not about lowering your standards. It’s about raising them. It’s about valuing honesty over hype and trusting that clear communication will serve you better than manufactured percentages.

The temptation to exaggerate is understandable. Job searching is stressful. You see other resumes with impressive numbers and worry yours looks weak in comparison. But most hiring managers would rather see a clear description of real work than a suspicious claim about improving something by an oddly specific percentage.

Start by reviewing your current resume with fresh eyes. Look for any numbers you’re not completely confident about. If you can’t explain how you arrived at a figure or defend it in an interview, remove it. Replace it with context that explains what you actually did and why it mattered.

Then look at your vague bullets. The ones that say you “improved” or “enhanced” or “optimized” something without explaining what that means. Add specifics. What was the problem? What did you change? What became possible afterward? You don’t need to rewrite everything, but every resume should have at least a few bullets that tell a complete story.

If you’re currently job searching, this approach might feel risky. You might worry that without big numbers, your resume won’t get past automated screening systems or won’t impress recruiters who are scanning dozens of applications. But remember what actually gets you hired. It’s not the resume that sounds most impressive. It’s the resume that leads to the best interview conversations.

When you write clearly about your work, you’re preparing yourself to interview well. You’ve already done the hard work of articulating what you contributed and why it mattered. You’re not scrambling to remember what that 47% improvement number was supposed to represent. You’re ready to have a real conversation about the problems you’ve solved.

For those early in their careers, this approach is even more important. You might not have years of experience to draw from. You might not have worked on high profile projects. But you have solved problems, written code, debugged issues, and learned from the work you’ve done. That’s enough if you describe it clearly.

Your resume is not a marketing document designed to oversell you. It’s a professional summary of what you’ve done and what you can do. Treat it that way. Be accurate. Be specific. Be clear. Trust that the right opportunities will come from presenting yourself honestly rather than trying to game the system with inflated metrics.

The goal is simple. When someone finishes reading your resume, they should understand what you’re capable of. They should be able to picture the kind of problems you solve and the level at which you operate. They should have enough information to decide whether you might be a good fit for their team.

That’s all a resume needs to do. It doesn’t need to be perfect. It doesn’t need to have the most impressive numbers. It just needs to be clear, honest, and well written. If you can do that, you’re already ahead of most people applying for the same roles.

Most resume advice stops at what to say. But knowing what NOT to say is just as important. Next, I will break down the subtle red flags that make hiring managers skeptical, the phrasing mistakes that undermine your credibility, and the specific language patterns that separate strong technical resumes from generic ones.

You'll also get a breakdown of how to handle gaps, career pivots, and situations where your title doesn't match your actual contributions.